Had the ban [on subversives] not been imposed to prevent Lim Chin Siong and other political detainees from standing as candidates in the 1959 elections, Lee and his faction in the PAP would have had to be more flexible and make compromises. This would have resulted in a government that placed democracy and human rights above all else. As a consequence political stability was achieved only by further repression and complete lack of concern for the rights of the individual to liberty and freedom. For this, the British must bear a heavy responsibility.

Mavis Puthucheary

When the new constitution for Singapore was drawn up to provide the country with internal self-government in 1958, it was to contain a clause preventing all political detainees from running as candidates in the first elections that would be held under the new constitution.

At the time it was assumed that the British authorities had insisted that this clause was a non-negotiable provision. But it was a contentious issue. According to Lee Kuan Yew, Lennox-Boyd [the Secretary of State for the Colonies] said that “her Majesty’s Government would not allow Singapore to come under communist domination and that he felt sure the Singapore delegation did not want this to happen anyway. He had therefore introduced a non-negotiable provision to bar all persons known to have indulged in or been charged with subversive activities from running as candidates in the first elections to be held under the new constitution. He[Lee Kuan Yew] objected to this, saying that:

“the condition is disturbing both because it is a departure from democratic practice and because there is no guarantee that the government in power would not use this procedure to prevent not only communists but also democratic opponents of their policy from standing for elections.” (Lee Kuan Yew: The Singapore Story pp 257-8)

Objections to the clause continued to be made when the All-Party delegation to the constitutional talks returned to Singapore. The only member of the Singapore Legislative Assembly who supported the clause was David Marshall. The enactment of this clause resulted in those arrested and detained under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance including Lim Chin Siong, were barred from contesting the elections held in May 1959.

Much later the Singapore public learned that Lim Yew Hock and Lee Kuan Yew had supported the clause in private although they opposed it in public. Lee himself gave a detailed account of what transpired. He said that what he said at the constitutional talks was only for the record:

“ In fact, Lim Yew Hock had quietly raised this matter with me back in Singapore after he had seen Lennox-Boyd in London in December, and Lennox-Boyd had already invited me to have tea with him alone at his home in Eaton Square to discuss it” (Lee Kuan Yew The Singapore story page 258)

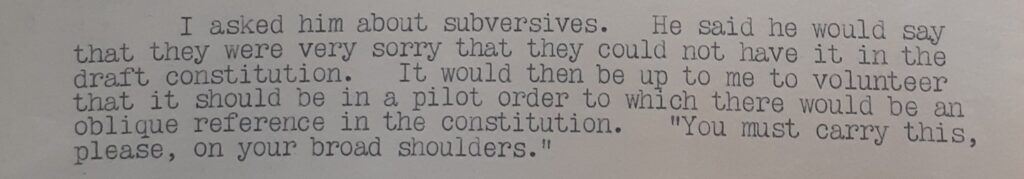

It was at this meeting that Lee expressed his view that should Lim Chin Siong and other political detainees stand as a candidates in the forthcoming election, the chances are that they would win their seats as by fighting for independence from colonial masters they have become extremely popular. Lennox-Boyd then asked him “Would you agree if I proposed this provision, that they be excluded from the first election to give the first elected government under the full internal self-government constitution a cleaner slate to start with?” To which Lee replied that he “will have to denounce it. You will have to take the responsibility” (ibid)

So some forty years later, we are told by Lee Kuan Yew that with the backing of the British officials, both Lim Yew Hock and Lee Kuan Yew had lied to the Singapore public. In February 1958 Lee Kuan Yew stated that “he (Lee kuan Yew) was a party with Lim Yew Hock in pressing the Secretary of State to impose a ban on detainees standing for election to the first legislature of the new constitution” (Singapore Political situation and outlook, February 1958 para 3 in FCO141/14766. Later, in May 1958 it was again stated that “Re the subversive ban which had been made at the express and urgent demand not only of Lim Yew Hock but also of Lee Kuan Yew…” (Notes on PREM11/2659 12 May 1958))

Lim Yew Hock and Lee Kuan Yew has each his own reasons for wanting to prevent Lim Chin Siong and other leftwing leaders from standing as candidates in the elections. As Labour Minister Lim Yew Hock had worked hard to create and maintain a strong trade union base in Singapore. He had helped bring the Singapore Trade Union Congress into being as early as September 1951 which was affiliated to the powerful International Congress of Free Trade unions (ICFTU) in America. But several trade unions were led by left-wing leaders and refused to be affiliated with the STUC. By 1955 when Lim Chin Siong and James Puthucheary became leaders of Factory and Shop Workers Union (SFSWU), the STUC unions were considerably weakened as the unions under the SFSWU increased in membership and strength. When Lim Yew Hock became Chief Minister he acted against the leaders of the trade unions affiliated to the SFSWU. Many leaders including Lim Chin Siong were detained. But he assumed that if they could be prevented from standing as candidates it would improve the chances of his political party winning seats in the next elections.

Lee Kuan Yew also wanted to prevent Lim Chin Siong and other left-wing leaders from standing as candidates in the next elections. Lim had been a very popular leader not only with the Chinese-speaking population in Singapore, but even within the PAP itself. At the third Annual PAP conference to elect a new Central Executive Committee in July 1956, Lim Chin Siong received the highest number of votes, with Lee Kuan Yew coming second. It was clear that should Lim Chin Siong stand as a candidate in the elections he would win his seat and Lee would find it difficult not to include him in his cabinet.

The answer to the question why did the British officials lend their support to a clause that was clearly undemocratic is more difficult to answer. In the past the only persons denied the opportunity to contest in elections were those who had been convicted of criminal offences. Political prisoners were always treated differently from convicted criminals. As they were been detained under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance which provided for detention without trial they could stand for elections while in prison. .

It seems that it was not the British but Lim Yew Hock and Lee Kuan Yew who insisted to the British that they would like to see such a clause in the new constitution. In his article entitled “Suppression of the Left in Singapore 1945-1963” (September 1997) Geoff Wade provides detailed information of a conversation between the then Australian Minister of Foreign Affairs (R.G. Casey) and Lim Yew Hock in which there appears to have been an understanding between Lim Yew Hock and Lee Kuan Yew. According to Sir Robert Black, Governor of Singapore, he was told by Lim Yew Hock that Lee Kuan Yew was keen on excluding Lim Chin Siong and other detainees from standing in elections. Black pointed out that this was not possible under the existing regulations as Sections 46 and 47 of the Order in Council were relevant to criminal convictions. But he emphasized that he agreed with the idea. “I emphasised that it was important in the interests of Singapore that Lim Chin Siong should not be able to fight an election from Changi jail” (24 January 1957, CO 1030 451 quoted in Greg Poulgrain in “Lim Chin Song in Britain’s Southeast Asian de-colonisation” Comet In Our Sky page 120)

The British officials agreed with the two Singapore leaders and began to think of ways and means to implement it. First they decided on the wording of the clause. In order to deflect attention from the fact that they were interfering in domestic politics and that the move was to prevent political opponents and rivals of Lim Yew Hock and Lee Kuan Yew, it was decided to ban people they called “subversives” without defining who they were. Second, in order to make it more palatable to liberal minded democrats in the House of Commons, it was decided to soften the undemocratic nature of the clause by stating that this ban was to apply only to the first election, The clause read “persons known to have been engaged in subversive activity should not be eligible for election to the first Legislative Assembly of the new State of Singapore”

These British civil servants also decided to cover themselves in case of any backlash by ensuring that the two Singapore leaders agreed to the ban. According to a letter from R Williams to the Commonwealth Relations Office dated 17 November 1958 the agreement regarding the subversive clause was not between the Secretary of State for the Colonies and the Singapore delegation but “in fact the agreement was between the Secretary of State and Lim Yew Hock and the Secretary of State and Lee Kuan Yew individually. They both visited the Secretary of State separately to negotiate the agreement. The rest of the Singapore all-party delegation did not know of the agreement” (CO1030/451)

Although the ban was valid for only one election, it had important implications for the development of politics in Singapore. The PAP won the first elections in May 1959 and, honoured its pledge of not taking office until the six top left-wing political detainees were released from jail. But none of them were members of the Legislative Assembly and were therefore not in the Cabinet. They were all members of the PAP but were unable to influence policy making in the Party because Lee Kuan Yew had made significant changes in the party constitution by introducing a cadre system which meant that they could not hold senior positions in the party unless they had the support of Lee Kuan yew and his colleagues. They therefore felt alienated from the party some of them had helped form in 1954 . With Lee Kuan Yew’s faction in control of party and the state, the leftwing turned to their traditional base, the trade unions. This produced tensions and conflict within the PAP finally resulting in the split in the PAP and the formation of the Barisan Socialis. Had the ban not been imposed to prevent Lim Chin Siong and other political detainees from standing as candidates in the 1959 elections, Lee and his faction in the PAP would have had to be more flexible and make compromises. This would have resulted in a government that placed democracy and human rights above all else. As a consequence political stability was achieved only by further repression and complete lack of concern for the rights of the individual to liberty and freedom. For this, the British must bear a heavy responsibility.